Supporting information for the Factors for Consideration

On this page

The need dimension

Need is about the disease, condition or illness. The Factors in this dimension describe the current health state, and does not consider the efficacy or impact of a proposed funding decision. Within the Need dimension we consider the impact of the disease, condition or illness on the person, their family or whānau, wider society, and the broader New Zealand health system.

We consider some the Factors within this dimension when evaluating the cost-effectiveness of a medicine or medical device. For more information on how we determine cost-effectiveness see Appendix 1.

The health need of the person

The health need of the person

- How unwell is a person with the health condition compared with an individual in perfect health?

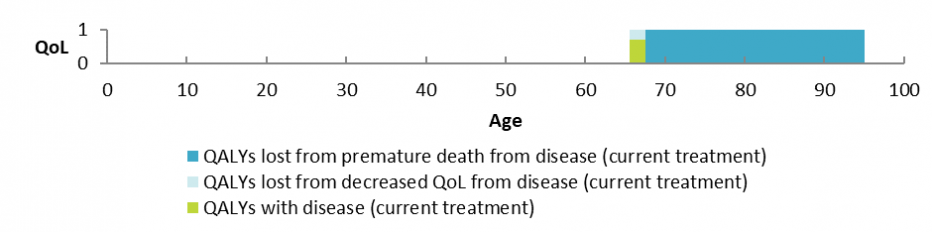

One major way in which we consider this is by comparing life expectancy and quality of life (QoL) at full health to life expectancy and QoL with the disease, condition or illness. In circumstances where an individual’s circumstances are unique (such as some applications considered under the Named Patient Pharmaceutical Assessment (NPPA) Policy) we will consider the health need of that individual person in isolation. Below is an example of a health need graph, which further describes this severity concept using a fictional example. Analyses of this type help us to consider the health need of the person.

The availability and suitability of existing medicines, medical devices and treatments

This Factor considers two important aspects:

- What options are currently publicly funded to treat the population with this condition?

- How well do the current options work?

A medicine is generally considered to be ‘available’ if it is listed on the Pharmaceutical Schedule. Medical devices and other treatments (for example, physiotherapy, nutrition advice, counselling) will generally be considered ‘available’ if they are used as part of standard practice within DHB hospitals or the community.

When thinking about the 'suitability' of available pharmaceuticals and treatments, we consider the practicality, effectiveness or appropriatness in the patient population group.

Relevant things that could determine the suitability of currently available treatments may include, for example, ease of use, required clinician skill and training, and the overall impact of change on the person using the device - insofar as these considerations may impact on health outcomes. The suitability of a pharmaceutical being proposed is noted in the Suitability dimension.

The health need of others

The health need of others

- What are the health needs for the family or whānau of the person with the disease, condition or illness? And the health needs for wider society?

As well as the needs of people with the health condition, there are also the effects of that person’s illness on the people around them – caregivers, family, whanau and wider society. Illness or disability may impact directly on these people too.

For example, those living with, or caring for, a person with an infectious disease are at risk of being infected and hence risk having a health loss. And there can be health needs for wider New Zealand society, for example, microbes that become resistant to antibiotics (‘superbugs’) eventually risk the health of the whole New Zealand population.

The impact on the Māori health areas of focus and Māori health outcomes

The impact on the Māori health areas of focus and Māori health outcomes

- Has the disease, condition or illness been identified as a Māori health area of focus?

- What is the impact of the disease, condition or illness on Māori health outcomes?

The intent of this Factor is to specifically consider Māori health need, in doing so representing Pharmac's commitment to being a good Te Tiriti o Waitangi partner.

There are two important considerations to this Factor. The first consideration is whether the disease, condition or illness itself has been identified as a health area of focus by Māori (as outlined in Te Whaioranga. Te Whaioranga was developed in partnership with Māori. The strategy will be updated regularly to ensure we address the health needs of Māori as identified by Māori.

Hauora Arotahi Māori health areas of focus

-

Hauora hinengaro Mental health

-

Matehuka Diabetes

-

Manawa Ora Heart health-high blood pressure and stroke

-

Romaha Ora Respiratory Health

-

Mate Pukupuku Cancer – Lung and Breast

In addition to health areas specifically identified as important to Māori, we also consider when a condition disproportionately affects Māori. We also think about differences in progression of disease, delayed treatment issues, disparities in timely access to treatment, of whether the condition affects Māori significantly more than it does other New Zealanders.

The impact on the health outcomes of population groups experiencing health disparities

The impact on the health outcomes of population groups experiencing health disparities

- What is the impact of the disease, condition, or illness on other population groups already experiencing health disparities?

- To what extent does the disease disproportionately affect populations that have substantive health disparities compared with the rest of the New Zealand population?

Equity is the underlying principle of this Factor, where we consider the impacts of a disease, condition, or illness on population groups who already experience health disparities.

We consider health disparities to be 'avoidable, unnecessary and unjust differences in the health groups of people'. Population groups experiencing health disparities will have one or more shared characteristics that mean they experience poorer health outcomes as a result of broader systemic social determinants of health, compounded by reduced access to the health system and unwarranted treatment variation. This disadvantage may mean that the population group may be more susceptible to a given illness, or may experience poorer health outcomes, than the average person with the illness. As well as considering if a population group is relevant to this Factor, we also research how great the disparity is.

When we consider if a population group is relevant to this Factor, we think about the following:

- What is the shared characteristic(s) that defines this population group?

- Are the health disparities experienced by this population group the result of broader systemic social determinants of health, or poorer access and treatment within the health system?

- Are the reasons for the identified disparity avoidable, unnecessary AND unjust? Consider whether particular population groups are more likely to receive treatment later than others, which means that second and third lines of treatment might be more important.

We may consider population groups in terms of geographical or socioeconomic characteristics in addition to ethnic or cultural characteristics. This may also include, but is not limited to, population groups outlined on the Ministry of Health website(external link)(external link).

The impact on Government health priorities

The impact on Government health priorities

- Is the disease, condition, or illness a government health priority?

We need to make sure our funding decisions help achieve the overall health priorities identified by the Government.

In line with Pharmac's Operating Policies and Procedures, these have been selected from strategic health sector documents. The list will be updated to reflect changes in priority.

The health benefit dimension

The health benefit dimension

The health benefit dimension looks at what health benefits (or losses) would arise from the proposed pharmaceutical. Health benefits are generally considered in relation to an average person with the condition, illness or disease. In circumstances where an individual has unique clinical circumstances, for example for some Named Patient Pharmaceutical Assessment (NPPA) applications, the health benefit may be considered in relation to the individual in question.

Under this Factor, we will consider the health benefits (or losses) to the person receiving the medicine or medical device, the health benefits to their family, whānau and wider society, and the consequences for the broader health system.

We also consider all the Factors within this dimension when evaluating the cost-effectiveness of a medicine or medical device. For more information on how we determine cost-effectiveness see Appendix 1.

The health benefit to the person

The health benefit to the person

- What would the health benefits be to the person who would receive the medicine, medical device or treatment that is being proposed?

Pharmac considers the health benefits of a pharmaceutical in relation to how much longer the person may live and any effects on their quality of life as a result of the treatment. Information on the health benefits of a medicine or medical device are provided by suppliers and other applicants in the funding applications we receive from them. We also get clinical advice regarding this Factor from our expert advisory committee, the Pharmacology and Therapeutics Advisory Committee (PTAC), and various specialist subcommittees of PTAC, or other sources of advice where relevant.

The health benefits from the medicine or medical device must be specific to the treatment being considered. For pharmaceuticals being considered for listing on the Pharmaceutical Schedule, the health benefit is considered in relation to the average person within the group who would receive the treatment.

The health benefit to family, whānau and wider society

The health benefit to family, whānau and wider society

- What would the health benefits be for the family or whānau of the person receiving the treatment, and for wider society?

A medicine or medical device may have health benefits for people other than the person receiving the treatment. In some cases this may impact directly on the health of the family and whānau (including caregivers). For example, effective treatment of an infectious disease is likely to have health benefits for those living with, or caring for, the person receiving the treatment as it reduces the chance of the disease being transmitted.

We also take into account the health benefits to the wider New Zealand society. For example, vaccines have health benefits for the wider population as they lower the risk of the spread of disease (known as ‘herd immunity’). Another example is antibiotic resistance where reducing the chance of resistance will have positive health benefits for the wider New Zealand population.

Consequences for the health system

Consequences for the health system

- If the proposal was funded, what would be the consequences for the health system?

- Does the proposal relate to any of the Government's priorities for the health system?

Pharmac’s decisions can have flow-on impacts for the rest of the health system; this Factor considers the potential consequences of a decision for the wider health system. For example the funding of a pharmaceutical that can be delivered in the community may free up resources in hospitals which could lead to greater efficiencies to the health system.

This Factor for Consideration does not include benefits or risks beyond the health system such as potential benefits to the justice system or the environment (at least those that don’t affect health), as this is outside of Pharmac’s Statutory Objective; to secure for eligible people in need of pharmaceuticals the best health outcomes that are reasonably achievable from pharmaceutical treatment and from within the funding provided.

We also consider the Government's strategic intentions for the health system under this Factor, to ensure alignment across the system. A proposal might positively or negatively impact on a Government health system priority.

In line with Pharmac's OPPs, the Government's health system priorities have been selected from strategic health sector documents and will be updated as priorities change.

The costs and savings dimension

The costs and savings dimension

This dimension focuses on the health-related costs and savings that would result from a decision to fund a medicine or medical device.

We consider the costs and savings to the person and their family, whānau and to wider society. The cost and savings to the health system covers both the cost and savings to the pharmaceutical budget and to the wider health system.

Where relevant, we may also consider the Factors within this dimension when evaluating the cost-effectiveness of a medicine or medical device. More information on how we determine cost-effectiveness can be found in Appendix 1.

Health-related costs and savings to the person

Health-related costs and savings to the person

- What would the health-related costs and savings be for the person who would be treated with the medicine or medical device that is being considered?

We consider the health-related costs and savings that may be experienced by the person receiving the medicine or medical device; for example, the amount a person pays for a GP visit to be able to access the medicine or medical device, pharmaceutical co-payments, home-based care or continuing care in a rest home.

When considering treatments for listing on the Pharmaceutical Schedule, we assess those costs and savings that are attributable to the average person with the illness, condition or disease. For an individual person (ie, being considered through the Named Patient Pharmaceutical Assessment Policy) the health-related costs and savings must be attributed to the individual, and specifically in relation to the pharmaceutical being considered for funding.

We do not take into account:

- The price of the medicine or medical device if the person was to purchase it privately (ie if it was not subsidised).

- The cost of the persons’ time off work (ie lost wages) and reduced productivity costs (as this could disadvantage treatments for those not in paid employment, such as the elderly and children and those who are chronically ill and/or disabled).

Further information on why the above costs are not considered is discussed in the Prescription for Pharmacoeconomic Analysis(external link).

Health-related costs and savings to the family, whānau and wider society

Health-related costs and savings to the family, whānau and wider society

- What would the health-related costs and savings be to the family or whānau of the person receiving the medicine or medical device, or to wider society?

Funding a medicine or medical device may result in health-related costs and savings to the family or whānau of the person receiving the treatment. For example, family or whānau may be permanent (or part-time) caregivers, and a treatment may alleviate the need for this level of care, and the costs associated with this.

When the person is dependent on family or whānau, for example children, they may not experience personal costs (as captured under the Factor ‘health-related costs and savings to the person’) but their caregivers might. Such costs and savings would be captured under this factor.

As for the ‘health-related costs and savings to the person’, we don’t count all possible costs and savings to the family, whanau or wider society. We do not take into account:

- the price of the medicine or medical device if the family or whānau was to choose to purchase it privately (ie if it was not subsidised)

- the cost of family or whānau time off work (ie lost wages) and reduced productivity costs (as this could bias against those not already in paid employment, such as the elderly and those who are chronically ill and disabled)

- cost of premature mortality to the economy (as this could ignore the impacts on those not in paid employment, who would not have the opportunity to forgo future potential earnings and tax contributions)

Further information on why these Factors are not considered is discussed in the Prescription for Pharmacoeconomic Analysis(external link).

Costs and savings to pharmaceutical expenditure

Costs and savings to pharmaceutical expenditure

- How would funding the medicine or medical device impact on pharmaceutical expenditure?

- Would funding this medicine or medical device result in some savings due to people switching from another pharmaceutical that is already funded?

We consider the costs of pharmaceuticals in this Factor, which covers both the Combined Pharmaceutical Budget and expenditure impact for hospital medicines and medical devices. In doing this, we also consider the impact that funding a pharmaceutical would have on future availability and funding, both of the pharmaceutical being considered and of other pharmaceuticals.

Only direct costs of pharmaceuticals are included. Surrounding costs such as diagnositc testing, training, and pharmacy mark-ups, are covered by the 'costs and savings to the rest of the health system' Factor.

Direct costs associated with medical devices can be different from those associated with medicines. This can include things like maintenance, outsourcing requirements, and costs that may be associated with ensuring the compatibility of the device with clinical and IT environments.

Costs and savings to the rest of the health system

Costs and savings to the rest of the health system

- Would the funding of the medicine or medical device create costs or savings for the rest of the health system?

A medicine or medical devices may reduce costs in the wider health system. For example if a treatment can be given at home rather than in hospital it would free up a hospital bed for someone else to use. Similarly, if a treatment could be self-administered rather than administered by a nurse, the nurse’s time would be freed up to use on something different. We call these ‘cost offsets’ and we include them in our analysis of the relative cost-effectiveness of a proposed medicine or medical device. This supports the health system to get better health outcomes from its resources.

We also take into account costs such as diagnosis, the cost of a patient stay in hospital, distribution costs (such as pharmacy mark-ups and dispensing fees) when considering cost and savings to the rest of the health system.

The suitability dimension

The suitability dimension

This dimension considers the non-clinical features of a medicine or medical device that may make it more suitable for people who would use it.

The features of the medicine or medical device that impact on use by the person

The features of the medicine or medical device that impact on use by the person

- What features of the medicine or medical device may impact use by the person receiving the medicine or medical device?

- Is the medicines of medical device registered for the condition that funding is being sought for?

This Factor looks at features associated with the medicine or medical device that would impact on use by the person receiving it. Suitability features can include things such as size, shape, taste, ease of use, or method of delivery (eg oral vs injection). These are examples of features of a medicine or medical device that could have an impact on health outcomes, particularly if they impact on adherence. For example if a capsule is very large, some people may not be able to swallow it. This could result in people not adhering to their medicine regimen which in turn affects their health outcomes.

The features of the medicine or medical device that impact on use by family, whānau and wider society

The features of the medicine or medical device that impact on use by family, whānau and wider society

- What features of the medicine or medical device may have an impact on use by the family or whānau of the person receiving the medicine or medical device, or wider society?

- Are there certain features of the medicine or medical device which would impact on the health outcomes if the pharmaceutical has to be given by someone other than the patient?

When family, whānau or members of wider society are the primary caregivers of a person receiving a medicine or medical device, the features of the medicine or medical device may impact their ability to give the treatment. This in turn may impact the person’s health outcomes. For example, it may be easier for caregivers to give a sick person a pill or oral liquid rather than an injection.

The features of the medicine or medical device that impact on use by the health workforce

The features of the medicine or medical device that impact on use by the health workforce

- What features of the medicine or medical device may have an impact on use by the health workforce?

How the health workforce uses the medicine or medical device may impact on the health of the person. For example how easy the medicine or medical device is to use for a health worker may reduce the likelihood of error or accident. Features of a medicine or medical device that are relevant to the health workforce could include things such as packaging, training in use, or ease of obtaining patient cooperation.

More information

The Factors support our decision-making model. We have a number of policies and processes that also inform our work.